- 2.1 Rationale for the Canada–United States Safe Third Country Agreement

- 3.1 Emergence of the Safe Third Country Concept in Canada

- 3.2 International Application of the Safe Third Country Concept

- 4.1 Review of the Implementation of the Canada–United States Safe Third Country Agreement

- 4.2 Stakeholder Perspectives

- 4.3 Legal Challenges

- 5.1 Expansion of the Agreement by the Additional Protocol

- 5.2 Data and Context

Executive Summary

Refugees are people who flee their countries because they have a well-founded fear of persecution. Once refugees arrive in another country and seek asylum, international law protects them from being sent back to face serious threats.

Of course, not all asylum claims are successful. Some asylum seekers may not meet the legal definition of a refugee. In other cases, errors or unfairness occur in a country’s assessment of the asylum claim. For various reasons, some asylum seekers pass through multiple countries and make claims in more than one of them.

Among countries with similar legal standards, evaluating the same person’s claims separately may be considered inefficient. To avoid this, some countries have agreements requiring people to claim asylum only in the first “safe” country they enter. In 2002, Canada and the United States (U.S.) agreed to this type of system, through what is known as the Safe Third Country Agreement (STCA).

As a result of the STCA , most people who come to Canada via the U.S. cannot claim asylum in Canada, although there are some exceptions, including for unaccompanied minors and for family members of Canadian citizens or permanent residents. In addition, until March 2023, the STCA applied only at official land border crossings.

Beginning in 2017, more asylum seekers began crossing the border into Canada through unofficial border crossings, circumventing the application of the STCA and allowing them to make a claim for refugee protection. Consequently, while some parties renewed their advocacy for broadening the STCA to apply to these types of crossings, others argued for suspending the agreement so that Canada could assess asylum claims independently of U.S. decisions.

In March 2023, the governments of Canada and the U.S. announced an additional protocol to the STCA which expanded the scope of the STCA to apply to the entire land border – including certain bodies of water – and not just official land border crossings. Under the revised agreement, individuals who cross the border between official ports of entry are ineligible to apply for asylum in the first 14 days after their arrival and may be returned to the U.S. during this period, if they do not qualify for an exception. The Additional Protocol to the STCA took effect on 25 March 2023.

In June 2023, a challenge to the constitutionality of the STCA culminated with the Supreme Court of Canada’s finding that the designation of the U.S. as a safe third country does not breach the rights to life, liberty and security of the person under section 7 of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms (Charter). However, the Court declined to determine whether this designation breaches equality rights under section 15 of the Charter – a separate issue that remains before the courts.

1 Introduction

Canada’s cooperation with the United States (U.S.) on matters relating to people claiming refugee protection has been a subject of significant debate over the past several decades. 1 This paper provides an overview of the Agreement between the Government of Canada and the Government of the United States of America for cooperation in the examination of refugee status claims from nationals of third countries, commonly referred to as the Canada–U.S. Safe Third Country Agreement (STCA). 2 It examines the fundamental aspects of the STCA , the historical and international context of the safe third country concept and the legal challenges that the STCA continues to face. Finally, it discusses the Additional Protocol to the STCA , which took effect in March 2023 and expanded the scope of the agreement.

2 The Canada–United States Safe Third Country Agreement

In refugee law, a “safe third country” 3 is a country in which an individual who passed through could have made a claim for refugee protection. According to the Government of Canada, only countries that respect human rights and offer a high degree of protection to refugee claimants may be designated as safe third countries. 4

As part of the U.S.–Canada Smart Border Declaration and associated 30-Point Action Plan, 5 Canada and the U.S. signed the STCA in December 2002, and it came into effect in December 2004. The agreement provides that persons seeking refugee protection must make a claim in the first of the two countries they arrive in, unless they qualify for an exception.

The exceptions to the STCA are set out in article 4 and fall into four general categories:

- unaccompanied minor exceptions;

- family member exceptions, such as having a spouse or parent who is already a citizen or permanent resident;

- document holder exceptions, such as having a valid work or study permit; and

- public interest exceptions, such as facing the possibility of a death sentence in the U.S. 6

For refugee claimants entering Canada, qualifying under one or more of these exceptions simply means that Canada – rather than the U.S. – will assess the claim. In addition, refugee claimants must still meet all other eligibility criteria 7 of Canada’s immigration legislation. For example, a person seeking refugee protection will not be eligible to make a refugee claim in Canada if that person is inadmissible to Canada on grounds of security, human or international rights violations, or criminality. 8 As such, individuals making a claim in either country, after having qualified for an exception, will not be removed to another country until a determination of that person’s claim has been made.

Before March 2023, the STCA applied only to refugee claimants who were seeking entry into Canada from the U.S. at a land port of entry, with very limited application in airports. 9 Since 2001, Canada has relied on strict border control measures implemented abroad in order to limit access to its territory through regular air and water passages. 10

The authority for the STCA stems from section 101(1)(e) of the Immigration and Refugee Protection Act (IRPA), which outlines the criteria that the Minister of Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship must apply to designate a country as a safe third country. To date, the U.S. is the only country that Canada has designated as a safe third country under the IRPA .

The IRPA requires that the federal government continually review countries designated as safe third countries to ensure that the conditions leading to the original designation continue to be met. 11 For example, a pattern of human rights violations by a safe third country could lead to a change in its designation. According to the latest directives issued in June 2015, the minister must review, on a continual basis, the factors listed in section 102(2) of the IRPA with respect to the U.S IRB . 12

2.1 Rationale for the Canada–United States Safe Third Country Agreement

Due to their geographical proximity and high level of interdependence, Canada and Mexico directly feel the effects of the U.S. border policies, which in the 1990s and early 2000s led to “the idea of a North America security perimeter.” 13 While Mexico was “deemed unsuitable for a such a project,” 14 Canada and the U.S. started exploring the possibility of establishing a security perimeter around the two countries. The 11 September 2001 (9/11) attacks on the U.S. accelerated these discussions, reinforced the importance of border security and highlighted the corresponding challenges of ensuring the efficient flow of people across the Canada–U.S. border. In a December 2001 joint Canada–U.S. Statement on Common Security Priorities, the implementation of a safe third country agreement was highlighted as part of a commitment to border security. 15 The statement claimed that by allowing either country to return a refugee claimant to the other country for assessment, asylum systems would be able to focus on genuine refugees in need of protection. 16

The federal government’s news release announcing the coming into force of the STCA in 2004 stated its objective as follows:

[T]o create an effective measure of control, necessary to better manage access to Canada’s refugee determination system. In fact, the agreement will enhance the orderly handling of refugee claims and strengthen public confidence in the integrity of the asylum systems of both countries. 17

At that time, the federal government was concerned by the number of refugee claimants coming to Canada from the U.S. It was noted that approximately one-third of all refugee claims in Canada from 1995 to 2001 were made by refugee claimants known to have arrived from or through the U.S. 18 Individuals making claims for protection in multiple countries was also a matter of concern 19 in a context in which the government felt there were “significant pressures on asylum systems in developed countries.” 20

3 The Concept of a Safe Third Country

Academic research shows that, especially since the end of the Cold War, countries have introduced increasingly restrictive migration policies and measures that aim to discourage the arrival of foreign nationals on their territory. These policies and measures include the imposition of visas and externalized border management practices. 21 The safe third country concept demonstrates that borders are not static; they are “developed and retooled through legal decision making.” 22 Borders respond to unique issues and policy objectives for a particular geography and population. The safe third country concept is applied on a transnational scale, requiring states to collaborate and share information to implement their migration enforcement practices. 23

In response to requests by courts, national authorities, lawyers and nongovernmental organizations, and in line with its supervisory function, 24 the United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) publishes position papers outlining practices and conditions in countries. The UNHCR specifies that it “does not pass a [judgment] as to whether a country can be considered ‘safe’ or not, and leaves it to the user of such papers to draw conclusions.” 25

In 1996, the UNHCR published an analysis of the safe third country concept. It included factors that countries should consider before determining that a refugee can legally be returned to a purportedly safe country. These factors include whether the third country has ratified and is in compliance with international refugee and human rights instruments, in particular the principle of non-refoulement; 26 the third country’s readiness to permit refugee claimants to remain in the country while their claims are examined on the merits; the third country’s adherence to basic human rights standards for the treatment of refugee claimants and accepted refugees; and the third country’s demonstrated willingness to accept returned refugee claimants and consider their claims fairly on the merits. 27

The UNHCR concluded that when these factors are given due consideration, such formal agreements can be advantageous for countries. For example, the safe third country concept could “reduce the misuse of asylum procedures, in particular multiple claims, as well as minimize the risk of the destabilizing effect of irregular movement of refugee claimants.” 28 However, it warned that

unilateral application of the safe third country concept, in the absence of a multilateral responsibility-sharing framework, may result in countries closer to the regions of origin being overburdened. 29

The UNHCR recalled that it is “in the interest of the international community to provide effective protection to refugees and to promote and find durable solutions for them,” based on more equitable and just responsibility-sharing. 30

3.1 Emergence of the Safe Third Country Concept in Canada

In 1985, in Singh v. Minister of Employment and Immigration, the Supreme Court of Canada declared that the legal guarantees to life, liberty and security of the person under section 7 of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms (Charter) apply to everyone physically present in Canada, regardless of their immigration status. 31 The Court also declared that refugee claimants have the right to an oral hearing of their protection claim before being either accepted into Canada or deported. 32 As such, the Singh decision drastically changed Canada’s immigration and refugee system.

The federal government introduced several legislative measures in 1987 that “sought to [clear up] the backlog of refugee claimants in Canada and reduce the amount of time required to adjudicate an application for refugee status.” 33 It also established the Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada (IRB), an arm’s-length administrative tribunal that adjudicates refugee claims.

As part of those legislative measures, Bill C-55, An Act to amend the Immigration Act, 1976 and to amend other Acts in consequence thereof, was introduced in the House of Commons, bringing forward the concept of a safe third country in Canadian legislation. Originally, under the safe third country principle, the bill had proposed that refugees arriving in Canada be excluded from the determination procedure and expelled if they failed to come directly to Canada from their state of origin. 34 However, amendments were introduced to

limit its application to persons who would actually be allowed to return to the intermediate country, or who would at least be allowed to have their refugee claims decided on the merits in the intermediate state. 35

This was to respect Canada’s international legal obligations toward refugees, including the principle of non-refoulement. 36 Bill C-55 came into force in January 1989. This introduced the concept of a safe third country in the Immigration Act, 1976, by enabling the federal government to list countries that Canada considered safe through future regulations.

In the same way that Bill C-55 set the legislative basis for the designation of a country as safe for the purposes of refugee adjudication, it was argued that it also “laid the groundwork for expanding the legal realm of ‘Canada’ for refugee applicants,” by pushing out Canada’s borders and “foreclosing any asylum adjudication for a country deemed safe or on behalf of an individual transiting through a safe country.” 37

In the early 1990s, the governments of Canada and the U.S. governments started discussions about a possible safe third country agreement between the two countries. In November 1995, both governments publicly released a “preliminary draft Agreement ‘For Cooperation in Examination of Refugee Status Claims from Nationals of Third Countries.’” 38 In undertaking a study on the issue, the House of Commons Standing Committee on Citizenship and Immigration (the committee) acknowledged that the refugee advocacy community opposed the preliminary draft agreement, but stated that “the underlying premises of the Agreement are sound” and exceeded the essential standards set out by the UNHCR. 39 In addition, the committee stated that

the exceptions to the general rules, in particular the recognition of the importance of family and the residual discretion reserved by each country to accept any refugee claim presented to it, provide sufficient flexibility and opportunity for humanitarian considerations to mitigate any harshness that might otherwise arise in its application. 40 [Emphasis in the original]

However, due to ongoing legislative changes to asylum law in the U.S. and to immigration and refugee law in Canada, the finalization of the agreement was delayed. 41 In 1996, the U.S. adopted its Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act. Canada’s new IRPA received Royal Assent on 1 November 2001.

The 9/11 attacks in the U.S. led to renewed negotiations. 42 In December 2001, Canada and the U.S. signed the Smart Border Declaration and its associated 30 Point Action Plan to enhance the security of our shared border while facilitating the legitimate flow of people and goods, which envisioned a safe third country agreement between the two countries. 43 In the same month, the committee recommended that Canada and the U.S. continue developing joint initiatives to ensure safe, secure and efficient border practices. It also recommended that

[w]hile maintaining Canada’s commitment to the Refugee Convention and our high standards in respect of international protection, the Government of Canada should pursue the negotiation of safe third country agreements with key countries, especially the United States. 44

This culminated in the STCA , which was signed in December 2002 and came into effect in December 2004.

3.2 International Application of the Safe Third Country Concept

Canada and the U.S. were not alone in pursuing these types of agreements during this period. 45 One of the most significant precursors to the STCA was the 1985 Schengen Agreement, which was initially signed by France, Germany, Belgium, Luxembourg and the Netherlands. 46 The Schengen Agreement sought to gradually abolish controls at the shared borders of these five countries. With respect to refugees, article 29 of the Schengen Agreement provided that only one country would have responsibility for processing any given refugee protection application, and that the responsible country would be determined by the criteria set out in article 30. In cases in which the criteria were not applicable, the default would be that the country in which the claim was first lodged would have responsibility for assessing it.

This concept has continued to expand and evolve over time, including through the Dublin Convention, which was initially ratified by the first 15 members of the European Union (EU), entering into force in 1997. Under the Dublin Convention, all EU member states were designated as safe countries for refugees. The Dublin Convention established comprehensive criteria to determine which country would be responsible for assessing refugee claims. The general rule under the Dublin Convention was that the first country that a refugee claimant entered would be responsible for assessing the claim. However, as with the STCA , this general rule was subject to several exceptions, including for situations in which the claimant had close family members in a different EU country. The aim of the Dublin Convention was to reduce the number of refugee claimants seeking asylum in multiple countries, including for economic or other reasons unrelated to their need for protection. 47 Since the Dublin Convention, there have been two new iterations of the legislation, the most recent being the 2014 Dublin III regulation. The aim remained the same, namely, to identify “the EU country responsible for examining an asylum application, by using a hierarchy of criteria such as family unity, possession of residence documents or visas, irregular entry or stay, and visa-waived entry.” 48

In 2020, the European Commission proposed the New Pact on Migration and Asylum that aims “to make the system more efficient, discourage abuses and prevent [unauthorized] movements,” including through increased cooperation in terms of capacity building and operational support. 49 While the criteria for determining the EU country responsible for examining an asylum application would remain unchanged, the EU member states agreed to implement “a voluntary, simple and predictable solidarity mechanism designed to support” their most affected counterparts “by offering relocations, financial contributions and other measures of support” 50 to ease the pressures caused by the large numbers of asylum seekers, refugees and other migrants.

Finally, in 2019, the U.S. signed asylum cooperative agreements with Guatemala, Honduras and El Salvador, 51 a first for the U.S. since signing the STCA with Canada. These new agreements allowed the U.S. to send certain asylum seekers at the U.S.–Mexico border back to Guatemala, Honduras and El Salvador to seek asylum there, rather than allowing them to apply for asylum in the U.S. However, those agreements were short-lived because in 2021, after the inauguration of a new administration, the U.S. suspended these agreements and terminated them subject to the required notice periods. 52

4 Challenges to the Canada–United States Safe Third Country Agreement since Implementation

With the entry into force of the STCA between Canada and the U.S. in December 2004, both governments faced several challenges. As stipulated in the agreement itself, a review of its implementation had to be conducted within the first year. 53 In addition, the STCA has been the subject of criticism and several legal challenges since its implementation, as detailed below.

4.1 Review of the Implementation of the Canada–United States Safe Third Country Agreement

The STCA required that Canada and the U.S., in cooperation with the UNHCR, conduct a review of the agreement and its implementation no later than a year after its coming into force. Accordingly, the UNHCR assessed the implementation of the STCA and examined how effectively its objectives were being met.

Released in June 2006, the UNHCR report provided a generally positive assessment of the STCA but raised some concerns for both countries to address. The primary areas of concern were as follows:

(1) lack of communication between the two Governments on cases of concern; (2) adequacy of existing reconsideration procedures; (3) delayed adjudication of eligibility under the Agreement in the United States; (4) in some respects, lack of training in interviewing techniques; (5) inadequacy of detention conditions in the United States as they affect asylum-seekers subject to the Agreement; (6) insufficient and/or inaccessible public information on the Agreement; and (7) inadequate number of staff dealing with refugee claimants in Canada. 54

The Canadian government responded to the UNHCR’s recommendations in November 2006, stating that it had “accepted, in whole or in part, 13 out of the 15 new or outstanding UNHCR recommendations.” 55 The two unfulfilled recommendations were the creation of an administrative review mechanism for “cases that may have been erroneously found ineligible” and the “broadening [of] the interpretation of article 6 to include … vulnerable persons who do not fall under any of the exceptions” to the STCA . 56 In both cases, the government argued that the existing mechanisms were sufficient and effective in ensuring a full and fair refugee determination process that captured all types of refugee claimants. In October 2007, in response to a parliamentary study, the federal government reiterated that most of the UNHCR’s recommendations had already been implemented and that others would be implemented in the future. 57

4.2 Stakeholder Perspectives

As noted in the Regulatory Impact Analysis Statement accompanying the regulations designating the U.S. as a safe third country, 58 some stakeholders, particularly non governmental organizations, have consistently opposed the STCA on principle. These stakeholders argue that refugees should have the right to choose where to seek protection, noting that the United Nations (UN) Convention relating to the Status of Refugees (Refugee Convention) does not require refugees to apply to the first safe country in which they arrive. There are a number of reasons a refugee claimant might choose to apply for refugee protection in a country other than the one of first arrival. Some of those reasons include the existence of extended family or support communities and language or cultural affinities in the country of choice. Further, some countries may interpret the definition of refugee more broadly to the benefit of a particular population, such as people seeking protection on the basis of sexual orientation. 59

Other concerns raised when the regulations were pre-published centred on whether the U.S. is in fact a safe country for refugees, as well as the perceived narrow scope of the exceptions and the potential for the STCA to increase incentives for irregular entry into Canada. While the final version of the regulations included some changes to the exceptions, the other concerns have persisted. For instance, a 2013 report prepared for the Harvard Immigration and Refugee Law Clinical Program found that refugee claimants have resorted to smugglers to help them circumvent the STCA . 60

Academics have also raised concerns about the STCA , which is seen as:

“pushing the border out,” to a distinct legal end where “Canada seeks to avoid its legal obligations, and in doing so, weakens the legal protections available to asylum seekers, under domestic and international legal instruments.” 61

Proponents of safe third country agreements suggest that such agreements are required to prevent those looking for refugee protection from “shopping” for a specific or preferred destination country. According to a researcher from the Centre for Immigration Policy Reform, the safe third country concept is based on the following principle:

[I]f someone flees their country of origin, they should seek sanctuary in the first safe country they are able to reach. If, however, they choose to move on to somewhere else to seek asylum, it indicates that their primary concern was not to reach safety but rather to be allowed to seek asylum and remain permanently in countries where there are generous benefits, high rates of acceptance, etc. In this regard they are considered to be “asylum shoppers.” 62

This justification is based on the premise that “asylum shopping” is equivalent to manipulating the international refugee system, and refugee claimants who are willing to manipulate the system may be less than truthful or genuine about their need for protection. 63

Such stakeholders have argued that the Canadian government did not go far enough with the STCA . For instance, it has been suggested that the STCA is flawed because there are too many exceptions to it. 64 Further, it was argued that the Government of Canada should enter into safe third country agreements with other countries as well, such as the United Kingdom, France and Germany. 65

4.3 Legal Challenges

While the UNHCR’s 2006 assessment of the STCA found that the U.S. sufficiently upholds its international obligations with respect to refugees, 66 advocates have pointed to differences between Canada and the U.S. to argue otherwise. Their concerns include migrant detention conditions, restrictions on refugee claimants’ ability to work pending hearings and the interpretation of the Refugee Convention and the UN Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (Convention against Torture). 67 Stakeholders have pointed to different acceptance rates for refugee claimants from certain countries, as well as the stronger protections Canada affords to victims of gender-based persecution. 68 Advocates have also suggested that refugee claimants in Canada have better access to legal aid and social assistance. 69 These concerns have been submitted to Canadian courts through multiple constitutional challenges.

After an unsuccessful challenge in 1989 due to lack of standing, 70 a second challenge was brought in 2004 by the Canadian Council for Refugees, Amnesty International and the Canadian Council of Churches, along with a Colombian refugee claimant in the U.S. 71 The applicants argued that the regulations designating the U.S. as a safe third country were invalid and unlawful, primarily because the U.S. does not comply with certain aspects of the Refugee Convention and the Convention against Torture. They argued that as a result, the STCA violates administrative law principles, the Charter and international law.

In 2007, the Federal Court found that the designation of the U.S. as a safe third country was unconstitutional. 72 This was based on a finding that the U.S. was not in compliance with its international obligations, such as non-refoulement, and that the application of the safe third country rule unjustifiably violated refugees’ Charter rights to life, liberty and security of the person (section 7) and to non-discrimination (section 15). The Court also found that the federal Cabinet had failed to comply with its obligation to ensure the continuing review of the status of the U.S. as a safe third country.

However, in 2008, the Federal Court of Appeal overturned this ruling, concluding that so long as the federal Cabinet gives due consideration to the four factors set out in section 102(2) of the IRPA 73 and accepts that the country in question is safe, the designation of a safe third country is not reviewable by courts. 74 Moreover, Cabinet’s obligation to continuously review the STCA must be focused on these four factors, and not necessarily on the general compliance of the U.S. with international law. Finally, the Federal Court of Appeal concluded that there was no factual basis to assess the Charter claims, since the refugee claimant in question had not attempted to enter Canada.

A subsequent constitutional challenge to the STCA was dismissed by the Federal Court of Appeal in 2019. In Kreishan v. Canada (Citizenship and Immigration), “ STCA -excepted” refugee claimants whose claims had been rejected by the Refugee Protection Division (RPD) of the IRB argued that they should be able to appeal their decisions to the Refugee Appeal Division of the IRB . 75 The Federal Court of Appeal rejected this argument, noting that international law does not mandate any particular form of appeal. It also stated that the question of whether some refugees have a more favourable appeals process has no bearing on whether “ STCA -excepted” refugee claimants’ rights were denied.

In 2017, the Canadian Council for Refugees, the Canadian Council of Churches and Amnesty International Canada, along with a Salvadoran woman accompanied by her children, 76 launched another legal challenge in the Federal Court about the designation of the U.S. as a safe third country for refugees. The organizations argued that the U.S. asylum system and immigration detention regime fails to meet required international and Canadian legal standards. 77 They argued that this situation results in substantial risk of detention, wrongful return to a country in which a refugee claimant would face persecution (refoulement) and other rights violations.

In July 2020, the Federal Court agreed with the applicants’ claim and found that the STCA unconstitutionally violates the rights to life, liberty and security of the person. 78 The Court noted that asylum seekers at land ports of entry receive no consideration of the substance of their refugee claims and are returned to the U.S. to face automatic detention, sometimes in solitary confinement or inhumane conditions, causing physical and psychological suffering. The Court emphasized that the STCA was supposed to be about the “sharing of responsibility” but fails to provide any guarantee of access to a fair refugee determination process. The Federal Court relied on the Supreme Court of Canada’s statement in Suresh v. Canada that the government “does not avoid the guarantee of fundamental justice merely because the deprivation in question would be effected by someone else’s hand.” 79

In April 2021, the federal government succeeded in its appeal of the decision. 80 The Federal Court of Appeal found that the claim had not been properly framed and thus could not be upheld.

In December 2021, the Supreme Court of Canada granted leave to appeal this decision, 81 and unanimously concluded in June 2023 that the relevant provisions of Canadian immigration law and regulations that enact the STCA do not breach the right to life, liberty and security of the person under section 7 of the Charter. 82

The Supreme Court ruled that the Federal Court failed to consider how various legislative safeguards – or “safety valves” – in the STCA framework and its enactment through Canadian law can protect against instances of fundamental unfairness. These include, for example, the administrative deferrals of removal orders, temporary resident permits and discretionary ministerial exemptions for specific individuals based on humanitarian and compassionate grounds or for groups of individuals through temporary public policies. 83 Moreover, regulations can further tailor the application of legislative provisions to prevent fundamentally unfair outcomes. These include, for example, section 159.6 of the Immigration and Refugee Protection Regulations, which prevents returning someone to the U.S. if they face charges or a conviction that could result in the death penalty. These types of safety valves can ensure that deprivations of liberty are not arbitrary or otherwise fundamentally unfair, even where differences exist between U.S. and Canadian law.

The Supreme Court also found that the Federal Court’s conclusion regarding the automatic detention of STCA returnees was erroneous, as the evidence did not demonstrate anything beyond a risk of discretionary detention. It also concluded that the record did not support the Federal Court’s finding that detention gives rise to a “real and not speculative” risk of refoulement from the U.S., as mechanisms are in place to advance or appeal a claim while detained. 84

Nevertheless, the Supreme Court allowed the appeal in part by remitting part of the case for relitigation before the Federal Court, due to insufficient evidence relating to claims under section 15 of the Charter. Specifically, the Federal Court did not make factual findings with respect to allegations that refugee claimants facing gender-based persecution and sexual violence are frequently denied refugee status in the U.S., contrary to the Refugee Convention.

Finally, the Supreme Court emphasized that its decision related to the constitutionality of the legislation itself, not to administrative conduct. It observed that decisions made by Canada Border Services Agency (CBSA) officers and other administrative decision-makers warrant “the most anxious scrutiny,” and can be the subject of individual claims. 85 Similarly, Cabinet’s obligation to ensure the continuous review of the U.S.’s designation as a safe third country was beyond the scope of the decision. 86

5 Renegotiation and Expansion of the Canada–United States Safe Third Country Agreement

In March 2023, Canada and the U.S. announced an Additional Protocol to the STCA that expanded its scope to apply across the entire land border, and not merely at official ports of entry. Individuals who cross the border between official ports of entry can be sent back to the U.S. within 14 days if they do not qualify for an exception.

The expansion of the STCA occurred in the context of increased irregular border crossings, as well as uncertainty about the future of the agreement due to an ongoing challenge to the constitutionality of the STCA . The following section explains the content of the expanded agreement, and provides context for these changes.

5.1 Expansion of the Agreement by the Additional Protocol

Long-standing concerns about the STCA prompted numerous calls for its suspension, while others advocated for its application regardless of how a refugee claimant crosses into Canada. 87 For instance, in 2011, officials from Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada (IRCC, at the time known as Citizenship and Immigration Canada) identified irregular border crossings as an area to examine during possible future changes to the STCA . 88

To modify the STCA , both Canada and the U.S. must agree to any changes in writing. In addition, either party may unilaterally suspend application of the STCA for a period of up to three months upon written notice to the other party. That suspension is renewable for additional periods of up to three months. 89 Stakeholders have argued that suspending the agreement could act as a test to measure the impact of its absence. 90

However, the federal government made it clear that it envisioned a future for the STCA , stating in 2018 that there would be “opportunities to negotiate and enhance a safe third country agreement that [would] operate more effectively to the mutual benefit of both countries.” 91 In 2021, the prime minister publicly mandated the Minister of Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship to continue working with the U.S. on modernizing the STCA . 92

In March 2023, Canada and the U.S. announced an Additional Protocol to the STCA that creates new binding international legal obligations for Canada, and amends how responsibilities are shared with the U.S. regarding processing asylum claims from irregular migration.

The Additional Protocol also expands the application of the STCA to migrants crossing irregularly between official ports of entry, but only applies within the first 14 days of their arrival. 93 These rules also apply to migrants crossing through designated bodies of water. 94 Although border measures limit access through water for ferries between Canada and the U.S., reports have indicated that human smugglers have been using waterways to enable migrants to cross irregularly into Canada. 95

The Additional Protocol sets out how Canada and the U.S. intend to adhere to the 14 day limit, outlining the requirements and related evidentiary burden applicable when a migrant is returned to the “country of last presence” to complete an asylum claim. 96

The concept of a 14-day limit originates from U.S. policy, stemming from a 2004 notice by the Department of Homeland Security (DHS), which authorizes the DHS to place in expedited removal proceedings certain foreign nationals (“aliens”) encountered within 14 days of entry and within 100 miles of any U.S. international land border. 97

The provisions of the Additional Protocol have been incorporated into the Immigration and Refugee Protection Regulations. 98 These updated regulations include several changes to definitions and interpretations in Canadian refugee law with respect to the application of the STCA and its exemptions. This includes a new definition for “stateless person” (section 159.1), and a new interpretation of “prior claim,” according to which asylum seekers who are initially deemed ineligible due to the STCA are exempt from such ineligibility if they are refused re-entry to the U.S. (section 159.01).

The most significant change is the addition of section 159.4(1.1) to the regulations, which establishes that the STCA is to be applied across the entire Canada–U.S. border, including bodies of water, and does not apply after an asylum seeker has been in Canada for 14 days or if the asylum seeker can demonstrate that one of the existing exceptions applies.

As part of the agreement surrounding the Additional Protocol, Canada agreed to accept 15,000 migrants from Central and South America through official channels between 2023 and 2024. According to media reports, these migrants will be regularized as resettled refugees through an upcoming special program. 99

In its Regulatory Impact Analysis Statement, the Government of Canada argued that the Additional Protocol will have several benefits, including supporting the standardized treatment of arrivals, increasing public confidence in the integrity of the asylum system, and “potentially reducing the volume of irregular arrivals” by deterring individuals from crossing irregularly. 100

However, the statement also acknowledged that the Additional Protocol could put asylum claimants at increased risk by creating incentives to avoid detection for 14 days. This could lead some to cross the border in more remote areas, increasing the risk of extreme weather conditions, and lack of access to food, water and basic services. Others may seek assistance from human smugglers, putting them at increased risk of human trafficking and sexual violence, which often disproportionately targets migrant women, girls, and LGBTQI individuals. 101

5.2 Data and Context

Since 1989 and the coming into force of the 1987 legislative measures discussed above, the federal government has tracked the number of refugee claims made in Canada. These in-Canada claims can be made either at a port of entry to the country or, within Canada, to a CBSA officer or the IRCC . 102 Individuals who cross the border at unofficial border crossings are generally intercepted and transported by the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP), first to the CBSA , to determine the admissibility of the claimant, and then, if successful, to the IRB to make a refugee claim. 103 The RCMP does not take any enforcement actions “against people seeking asylum as per section 133 of the Immigration and Refugee Protection Act.” 104 For this reason, those who cross the border at unofficial border crossings are commonly called irregular border crossers. As discussed above, until March 2023, the STCA applied only to refugee claimants who sought entry to Canada from the U.S. at land ports of entry.

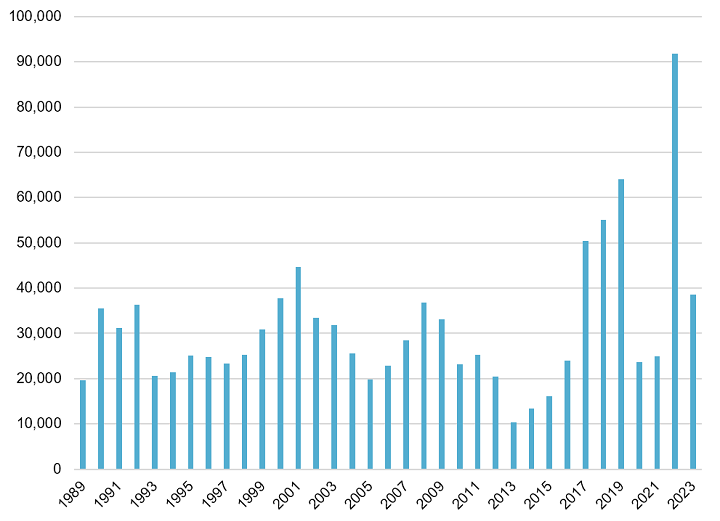

As seen in Figure 1, between 1989 and June 2023, the overall number of claims averaged around 31,684 per year; the lowest number of claims was registered in 2013 (10,378) and the highest in 2022 (91,850). Because of the COVID-19 pandemic and temporary Canada–U.S. border closures from March 2020 to November 2021, 105 fewer in-Canada refugee claims were registered in 2020 and 2021 (23,695 and 24,9105 respectively). 106

Figure 1 – Number of Refugee Claims Made in Canada, January 1989 to June 2023

000 claims received. The lowest number of claims, just over 10,000, was received in 2013." />

000 claims received. The lowest number of claims, just over 10,000, was received in 2013." />

Notes: The first source, below, provides no data on refugee claimants for 1988; consequently, the data series starts at 1989. In addition, the series in that source is broken from 1998 but has data from a more recent edition of the same source. The series is again broken from 2017 and has a different source. The data for 2023 are not complete. The terms “refugee claimants” and “asylum claimants” in the sources are used interchangeably and refer to people who have applied for refugee protection status in Canada.

Sources: Figure prepared by the Library of Parliament using data obtained from Citizenship and Immigration Canada, “Canada – Temporary residents by yearly status, 1988–2012,” Canada Facts and Figures: Immigration Overview – Permanent and Temporary Residents, 2012, p. 52; Government of Canada, “10.1. Asylum Claimants by gender, 1997 to 2017,” Facts and Figures 2017 – Immigration Overview – Temporary Residents; Government of Canada, Asylum claims by year – 2018; Government of Canada, Asylum claims by year – 2019; Government of Canada, Asylum claims by year – 2020; Government of Canada, Asylum claims by year – 2021; Government of Canada, Asylum claims by year – 2022; and Government of Canada, Asylum claims by year – 2023.

Increases in the number of claims made in Canada in 2017 and again in 2022 were in part due to people crossing the Canada–U.S. border at unofficial border crossings.

While the overall reasons 107 and full impact 108 of this increase in refugee claims from irregular border crossers are outside the scope of this paper, one reason that the increased volume is significant is its impact on the functioning of the IRB . The sudden increase in the number of claims referred to the IRB 109 has placed a strain on its resources. The IRB was already struggling to make decisions under prescribed timelines and dealing with a backlog of older claims. 110

A 2018 independent review of the IRB found that the prescribed timelines for holding hearings were met in only 59% of cases in 2017, down from a high of 65% between 2014 and 2016. The IRB reported that these delays were largely attributable to human resources challenges, including insufficient recruitment, and a more complex caseload due to a large variety of countries of origin. 111

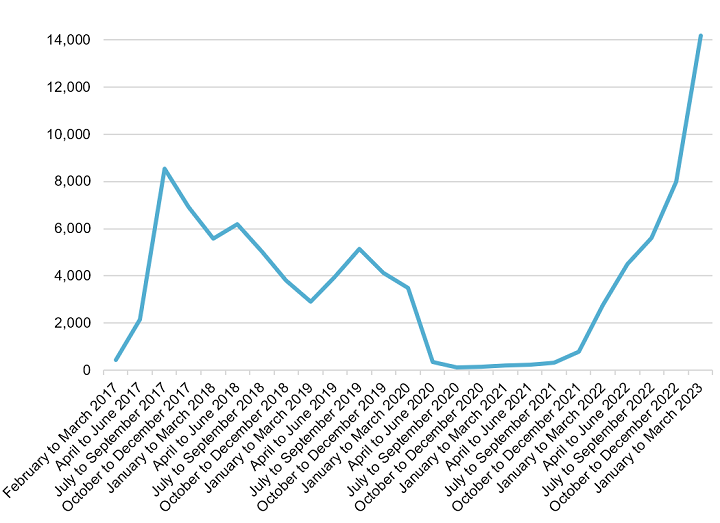

Prior to 2017, the IRB did not specifically track statistics on refugee claims made by irregular border crossers. Figure 2 provides an overview of the number of claims received by the IRB from people intercepted by the RCMP at unofficial border crossings. In 2020 and 2021, the IRB received a smaller number (4,154 and 1,552 respectively) of in-Canada refugee claims by irregular border crossers due to temporary Canada–U.S. border closures during the COVID-19 pandemic. 112 This was followed in 2022 by a record number of asylum seekers apprehended between ports of entry (39,540). 113 The highest number of claims received in a quarter was registered from January 2023 to March 2023 (14,192). 114

Figure 2 – Number of Refugee Claims Made by Irregular Border Crossers, February 2017 to March 2023

Note: The Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada (IRB) has only partial data for February 2017 and March 2017.

Source: Figure prepared by the Library of Parliament using data obtained from IRB , “Statistics on refugee claims made by Irregular Border Crossers, by Calendar Year and Quarter,” Irregular border crosser statistics.

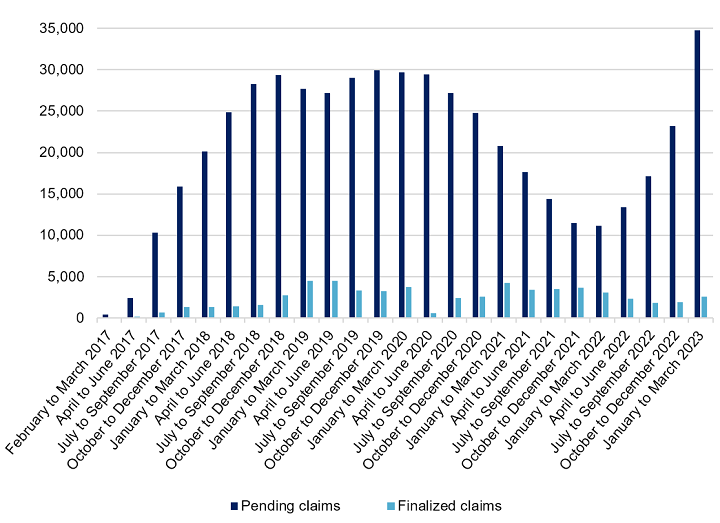

The IRB is dealing with significant backlogs, as seen in Figure 3. While the smaller number of claims received during the COVID-19 pandemic and temporary Canada–U.S. border closures temporarily reduced the number of pending claims, this trend was quickly reversed in 2022, and a new record high was reached in early 2023. From January 2023 to March 2023, 2,589 claims from irregular migrants were finalized by the IRB , while 34,781 claims were still pending in the system. Numbers are not yet available since the coming into force of the Additional Protocol. 115

Figure 3 – Number of Pending and Finalized Refugee Claims Made by Irregular Border Crossers, February 2017 to March 2023

Note: The Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada (IRB) has only partial data for February 2017 and March 2017.

Source: Figure prepared by the Library of Parliament using data obtained from IRB , “Statistics on refugee claims made by Irregular Border Crossers, by Calendar Year and Quarter,” Irregular border crosser statistics.

In 2018, the IRB established an inventory reduction task force for less complex claims, which focused on claims that “lend themselves to quicker resolution through paper-based or short hearing decisions.” 116 To increase its productivity and improve its case management approach, the IRB also updated its policy on the expedited processing of refugee claims by the RPD and issued instructions governing the streaming of less complex claims at the RPD. 117 As such, the IRB has established “shorter, more focused hearings to resolve straightforward claims and has also decided claims without a hearing, where appropriate.” 118

In addition to streamlining its processes, the IRB received, through Budget 2018, $74 million over two years to “enable faster decision-making on asylum claims, including money to hire 64 decision makers plus 185 support staff.” 119 As such, the IRB was able to finalize “30% more refugee claims, and over 60% more refugee appeals in fiscal year 2018 to 2019 than in the previous year.” 120

Also in Budget 2018, the Government of Canada provided about $100 million over two years for the IRCC, the CBSA, the RCMP and other concerned departments to address operational pressures resulting from irregular migration. 121 Those funds helped support “intake of new asylum claims, front-end security screening procedures, eligibility processing, removal of unsuccessful claimants, and detention and removal of those who pose a risk to the safety and security of Canadians.” 122

The IRB received a further investment of $208 million in Budget 2019 to increase its overall target for processed refugee claims to 50,000 per year. 123 In addition, the Economic and Fiscal Snapshot 2020 and Budget 2022 also allocated funding to the IRB as part of the federal government’s commitment “to support the long-term stability and integrity of Canada’s asylum system.” 124 These additional investments helped stabilize the IRB , which worked to reduce the backlog and wait time for refugee claims and appeals during the pandemic. 125

In Budget 2022, the IRB was allocated $600 million in funding over four years, and $150 million ongoing, plus additional funds over two years to process additional claims. 126

6 Conclusion

The STCA has been controversial from its inception. Its proponents have argued that it allows Canada and the U.S. to better manage access to the refugee determination process. Critics have argued that the U.S. is not safe for refugees and that sending asylum seekers to the U.S. without being able to have their claim assessed under Canadian refugee law is a violation of fundamental rights.

The recent expansion of the STCA is intended to increase the integrity of the refugee system by standardizing the treatment of arrivals and potentially reducing their volume. However, it may also create incentives that put asylum seekers at greater risk of harm. These developments highlight the barriers and uncertainty that refugees who hope to seek asylum in Canada face.

The Supreme Court of Canada’s decision confirmed that the designation of the U.S. as a safe third country does not violate right to life, liberty and security of the person under section 7 of the Charter. However, the Court did not render a decision with respect to section 15. Moreover, the Court confirmed that administrative and Charter relief remains available on an individual basis to persons whose rights are violated through any inappropriate application of the legislative scheme, including its various safety valves. It is therefore likely that the STCA will continue to be the subject of legal challenges and public debate.

Notes

- Refugee claimants are people who have applied for refugee protection status in Canada. They are also sometimes referred to as “asylum claimants” or “asylum seekers.” For the purposes of this paper, these terms are interchangeable. See Government of Canada, “Refugee Claimant,” Glossary. For more information on Canada’s refugee determination process, see Government of Canada, Claim refugee status from inside Canada: About the process. [ Return to text ]

- Government of Canada, Final Text of the Safe Third Country Agreement. [ Return to text ]

- Government of Canada, “Safe third country,” Glossary. [ Return to text ]

- Government of Canada, “Designation of Safe Third Countries,” Canada–U.S. Safe Third Country Agreement. [ Return to text ]

- United States (U.S.), Department of State, U.S.–Canada Smart Border/30 Point Action Plan Update, Fact sheet, 6 December 2002. [ Return to text ]

- Government of Canada, “Exceptions to the Agreement,” Canada–U.S. Safe Third Country Agreement. In 2009, Canada removed an exemption from the Canada–U.S. Safe Third Country Agreement (STCA) that permitted refugee claims to be filed at the Canadian border by foreign nationals from “moratorium countries,” which include countries to which Canada does not deport failed refugee claimants. See Regulations Amending the Immigration and Refugee Protection Regulations, SOR/2009-210, 23 July 2009, in Canada Gazette, Part II, 5 August 2009, and accompanying Regulatory Impact Analysis Statement, pp. 1470–1475. [ Return to text ]

- Immigration and Refugee Protection Act, S.C. 2001, c. 27, s. 101. [ Return to text ]

- There are 11 grounds for inadmissibility: security, violation of international or human rights, serious criminality, criminality, organized criminality, health grounds, financial reasons, misrepresentation, cessation of refugee protection, non-compliance with the Act and accompanying a family member who is inadmissible. Ibid., ss. 34–42. [ Return to text ]

- The STCA applies at airports only if the person seeking refugee protection in Canada has been refused refugee status in the U.S. and is in transit through Canada after being deported from the U.S. Until March 2023, it did not apply to those who crossed the border between ports of entry. A port of entry is defined in section 2 of the Immigration and Refugee Protection Regulations. See Government of Canada, “Where the Agreement is in effect,” Canada–U.S. Safe Third Country Agreement; and Immigration and Refugee Protection Regulations, SOR/2002-227, s. 2. [ Return to text ]

- Efrat Arbel, “Shifting Borders and the Boundaries of Rights: Examining the Safe Third Country Agreement between Canada and the United States,” International Journal of Refugee Law, Vol. 25, No. 1, 2013, pp. 76–77. [ Return to text ]

- Government of Canada, “Review of Safe Third Countries,” Canada–U.S. Safe Third Country Agreement. [ Return to text ]

- Government of Canada, Directives for ensuring a continuing review of factors set out in subsection 102(2) of the Immigration and Refugee Protection Act with respect to countries designated under paragraph 102(1)(a) of that Act (2015), Order in Council P.C. 2015-0809, 11 June 2015. [ Return to text ]

- Ruben Zaiotti, “Chapter 9, Beyond Europe: Toward a New Culture of Border Control in North America,” Cultures of Border Control: Schengen and the Evolution of European Frontiers, 2011, p. 204. This idea is widely implemented between Canada and the U.S. today following the formal declaration of a shared vision for perimeter security and economic competitiveness, which, in 2011, established

a new long-term partnership built upon a perimeter approach to security and economic competitiveness. This means working together, not just at the border, but beyond the border to enhance our security and accelerate the legitimate flow of people, goods and services.

[t]he prohibition for States to extradite, deport, expel or otherwise return a person to a country where his or her life or freedom would be threatened, or where there are substantial grounds for believing that he or she would risk being subjected to torture or other cruel, inhuman and degrading treatment or punishment, or would be in danger of being subjected to enforced disappearance, or of suffering another irreparable harm.

(a) whether the country is a party to the Refugee Convention and to the Convention Against Torture; (b) its policies and practices with respect to claims under the Refugee Convention and with respect to obligations under the Convention Against Torture; (c) its human rights record; and (d) whether it is party to an agreement with the Government of Canada for the purpose of sharing responsibility with respect to claims for refugee protection.

© Library of Parliament

- 44 th Parliament, 1 st Session

- 43 rd Parliament, 2 nd Session

- 43 rd Parliament, 1 st Session

- 42 nd Parliament, 1 st Session

- 41 st Parliament, 2 nd Session

- 41 st Parliament, 1 st Session

- 40 th Parliament, 3 rd Session

- 40 th Parliament, 2 nd Session

- 40 th Parliament, 1 st Session

- 39 th Parliament, 2 nd Session

- 39 th Parliament, 1 st Session

- 38 th Parliament, 1 st Session

- 37 th Parliament, 3 rd Session

- 37 th Parliament, 2 nd Session

- 37 th Parliament, 1 st Session